Life and work

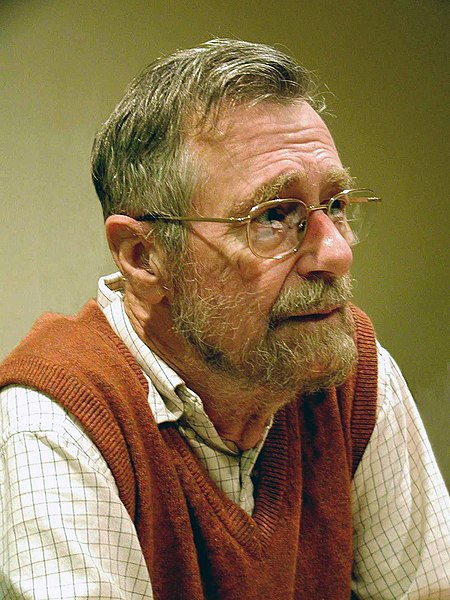

Born in Rotterdam, Dijkstra studied theoretical physics at Leiden University, but he quickly realized he was more interested in computer science. Originally employed by the Mathematisch Centrum in Amsterdam, he held a professorship at the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, worked as a research fellow for Burroughs Corporation in the early 1970s, and later held the Schlumberger Centennial Chair in Computer Sciences at The University of Texas at Austin, in the United States. He retired in 2000.

Among his contributions to computer science is the shortest path-algorithm, also known as Dijkstra's algorithm; Reverse Polish Notation and related Shunting yard algorithm; the THE multiprogramming system; Banker's algorithm; the concept of operating system rings; and the semaphore construct for coordinating multiple processors and programs. Another concept due to Dijkstra in the field of distributed computing is that of self-stabilization – an alternative way to ensure the reliability of the system. Dijkstra's algorithm is used in SPF, Shortest Path First, which is used in the routing protocol OSPF, Open Shortest Path First.

He was also known for his low opinion of the GOTO statement in computer programming, writing a paper in 1965, and culminating in the 1968 article "A Case against the GO TO Statement" (EWD215), regarded as a major step towards the widespread deprecation of the GOTO statement and its effective replacement by structured control constructs, such as the while loop. This methodology was also called structured programming, the title of his 1972 book, coauthored with C.A.R. Hoare and Ole-Johan Dahl. The March 1968 ACM letter's famous title, "Go To Statement Considered Harmful", [1] was not the work of Dijkstra, but of Niklaus Wirth, then editor of Communications of the ACM. Dijkstra was known to be a fan of ALGOL 60, and worked on the team that implemented the first compiler for that language. Dijkstra and Jaap Zonneveld, who collaborated on the compiler, agreed not to shave until the project was completed.

He also wrote two important papers in 1968, devoted to the structure of a multiprogramming operating system called THE, and to Co-operating Sequential Processes.

He is famed for coining the popular programming phrase "2 or more, use a for", alluding to the fact that when you find yourself processing more than one instance of a data structure, it is time to encapsulate that logic inside a loop.

From the 1970s, Dijkstra's chief interest was formal verification. The prevailing opinion at the time was that one should first write a program and then provide a mathematical proof of correctness. Dijkstra objected that the resulting proofs are long and cumbersome, and that the proof gives no insight as to how the program was developed. An alternative method is program derivation, to "develop proof and program hand in hand". One starts with a mathematical specification of what a program is supposed to do and applies mathematical transformations to the specification until it is turned into a program that can be executed. The resulting program is then known to be correct by construction. Much of Dijkstra's later work concerns ways to streamline mathematical argument. In a 2001 interview[citation needed], he stated a desire for "elegance", whereby the correct approach would be to process thoughts mentally, rather than attempt to render them until they are complete. The analogy he made was to contrast the compositional approaches of Mozart and Beethoven.

Dijkstra was one of the very early pioneers of the research on distributed computing. Some people even consider some of his papers to be those that established the field. In particular, his paper "Self-stabilizing Systems in Spite of Distributed Control" started the sub-field of self-stabilization.

Dijkstra was known for his essays on programming; he was the first to make the claim that programming is so inherently difficult and complex that programmers need to harness every trick and abstraction possible in hopes of managing the complexity of it successfully.

Dijkstra believed that computer science was more abstract than programming; he once said, "Computer Science is no more about computers than astronomy is about telescopes."

He died in Nuenen, The Netherlands on August 6, 2002 after a long struggle with cancer. The following year, the ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) PODC Influential Paper Award in distributed computing was renamed the Dijkstra Prize in his honour.

[edit] EWDs and writing by hand

Dijkstra was known for his habit of carefully composing manuscripts with his fountain pen. The manuscripts are called EWDs, since Dijkstra numbered them with EWD as prefix. Dijkstra would distribute photocopies of a new EWD among his colleagues; as many recipients photocopied and forwarded their copy, the EWDs spread throughout the international computer science community. The topics were mainly computer science and mathematics, but also included trip reports, letters, and speeches. More than 1300 EWDs have since been scanned, with a growing number also transcribed to facilitate search, and are available online at the Dijkstra archive of the University of Texas[2].

One of Dijkstra's sidelines was serving as Chairman of the Board of the fictional Mathematics Inc., a company that he imagined having commercialized the production of mathematical theorems in the same way that software companies had commercialized the production of computer programs. He invented a number of activities and challenges of Mathematics Inc. and documented them in several papers in the EWD series. The imaginary company had produced a proof of the Riemann Hypothesis but then had great difficulties collecting royalties from mathematicians who had proved results assuming the Riemann Hypothesis. The proof itself was a trade secret (EWD 475). Many of the company's proofs were rushed out the door and then much of the company's effort had to be spent on maintenance (EWD 539). A more successful effort was the Standard Proof for Pythagoras' Theorem, that replaced the more than 100 incompatible existing proofs (EWD427). Dijkstra described Mathematics Inc. as "the most exciting and most miserable business ever conceived" (EWD475). He claimed that by 1974 his fictional company was the world's leading mathematical industry with more than 75 percent of the world market (EWD443).[3]

Having invented much of the technology of software, Dijkstra eschewed the use of computers in his own work for many decades. Almost all EWDs appearing after 1972 were hand-written. When lecturing, he would write proofs in chalk on a blackboard rather than using overhead foils, let alone Powerpoint slides. Even after he succumbed to his UT colleagues’ encouragement and acquired a Macintosh computer, he used it only for e-mail and for browsing the World Wide Web.[4]

Some variants with replacement adjectives (considered silly, etc.) have been noted in hacker jargon.[9] Many variants dealt with computer-related issues, such as: "Weblogging Considered Harmful" [10] "'Reply-To' Munging Considered Harmful" [11] "XMLHttpRequest Considered Harmful" [12] "Letter 'O' Considered Harmful" [13] "Csh Programming Considered Harmful" [14] "Geek Culture Considered Harmful to Perl" [15]

Eric A. Meyer focused upon the letter, itself:

- "Considered Harmful" Essays Considered Harmful [16]

Others extended Rubin's criticism, of Wirth's refutation cliche, into a recursive sequence, starting with:

- "GOTO Considered Harmful" Considered Harmful' Considered Harmful

- "GOTO Considered Harmful" Considered Harmful' Considered Harmful considered harmful

- "GOTO Considered Harmful" Considered Harmful' Considered Harmful considered harmful considered harmful

- . . .

There is no obvious limiting condition to end this infinite sequence (nor any standard punctuation convention with which to represent it).

This recursive notion was reminiscent of (and may have been inspired by) a series of earlier letters that appeared in "MAD" magazine, beginning with:

- "The guy who writes your letters should write the rest of the magazine."

then, in a subsequent issue:

- "The guy who writes your 'The guy who writes your letters should write the rest of the magazine.' letters should write the rest of the magazine."

and, later:

- The guy who writes your "The guy who writes your 'The guy who writes your letters should write the rest of the magazine.' letters should write the rest of the magazine." letters should write the rest of the magazine.

Similar recursions were extended even further, in later issues of "MAD" magazine, during the late 1950s or early 1960s. These MAD magazine letters were published several years prior to Wirth's re-titling of the Dijkstra letter, and the further variations of it.

迪克斯特拉1930年出生于鹿特丹。他早期在欧洲和美国的职业生涯中便在航空和建筑学中做过首次计算机模拟。他的母亲是一位数学家,父亲是一位化学家。这种家庭背景使他把正规的逻辑定理和方法论应用到了计算机编程中。

迪克斯特拉是创造出Algol编程语言的委员会的成员。这个委员会还推出了许多支持Pascal、Basic和C语言的想法。他特别擅长识别和编写算法,并以编写了第一个Algol 60编译器而闻名。他发明或者帮助定义的创新思想包括,结构编程、堆栈、矢量、信号灯、同步进程和声名狼藉的死锁。死锁是多任务编程人员最害怕的,在死锁状态下,两个进程相互等待对方继续执行而处于停止状态。

Dijkstra的很多概念和词组丰富了计算机语言,如结构化编程,康采恩的分离,同步化,deadly embrace, 餐厅哲学家,最弱前置条件,guarded command, the excluded miracle以及有名的用来控制计算机进程的“旗语”。牛津英语词典则引用了他在计算信息处理技术语境中的“矢量”和“堆栈”的用法。

1962年,迪克斯特拉在Eindhoven Polytechnic大学担任数学教授。他当时不赞成把他的职位称作计算机科学,因为他认为计算机专业当时还不足以称作科学。

他从1967年开始把他的想法写成论文,到他去世的时候,他一共写了1,300篇论文,大多数论文都是用钢笔写的。

1973年,迪克斯特拉成为当时主要计算机公司之一的Burroughs公司的研究人员。1984年,迪克斯特拉成为德州大学的全职教授。

迪克斯特拉1972年获得了美国计算机协会图灵奖,这个奖通常被认为是计算机行业的诺贝尔奖。他是荷兰皇家科学与艺术学院的院士、美国科学与艺术学院的院士和英国计算机协会的最佳院士。2002年,日本C&C基金会承认,迪克斯特拉通过在基础软件理论、算法理论、结构编程和信号灯等领域的创造性的研究为计算机软件的科学基础作出了先驱性的贡献。

没有评论:

发表评论